How Prince Group’s Collapse Triggered a Shockwave Through Cambodia’s Scam Industry

- Global Anti-Scam Org

- Jan 12

- 4 min read

In late December 2025, renewed fighting along the Thailand–Cambodia border created the first major shock to Cambodia’s compound-linked ecosystem. Armed clashes erupted again near Poipet and O’Smach after a temporary pause in hostilities, with artillery fire, air strikes, and ground engagements affecting border towns on both sides. International reports confirmed that commercial and residential areas close to the frontier were hit or placed at risk, prompting evacuations and triggering large-scale movement away from the immediate conflict zone.

As the situation deteriorated near the border, groups operating out of O’Smach and Poipet began to flee. Some left because nearby buildings were damaged or threatened by ongoing strikes; others moved because transport routes were disrupted and local landlords advised tenants to relocate for safety. By the final week of December, buses were visibly moving people away from the frontier in significant numbers.

Chey Thom became one of the primary destinations. Unlike the border towns under fire, Chey Thom is far inside Cambodia and close to Phnom Penh. Its distance from the fighting made it appear safer, and its proximity to the capital gave the impression of greater stability. This perception—not any official designation—drew large numbers of displaced groups into the district during late December and early January. For a brief moment, Chey Thom became the fallback zone for those escaping the border conflict.

The Second Wave: Extradition Shock and Sudden Flight From Chey Thom

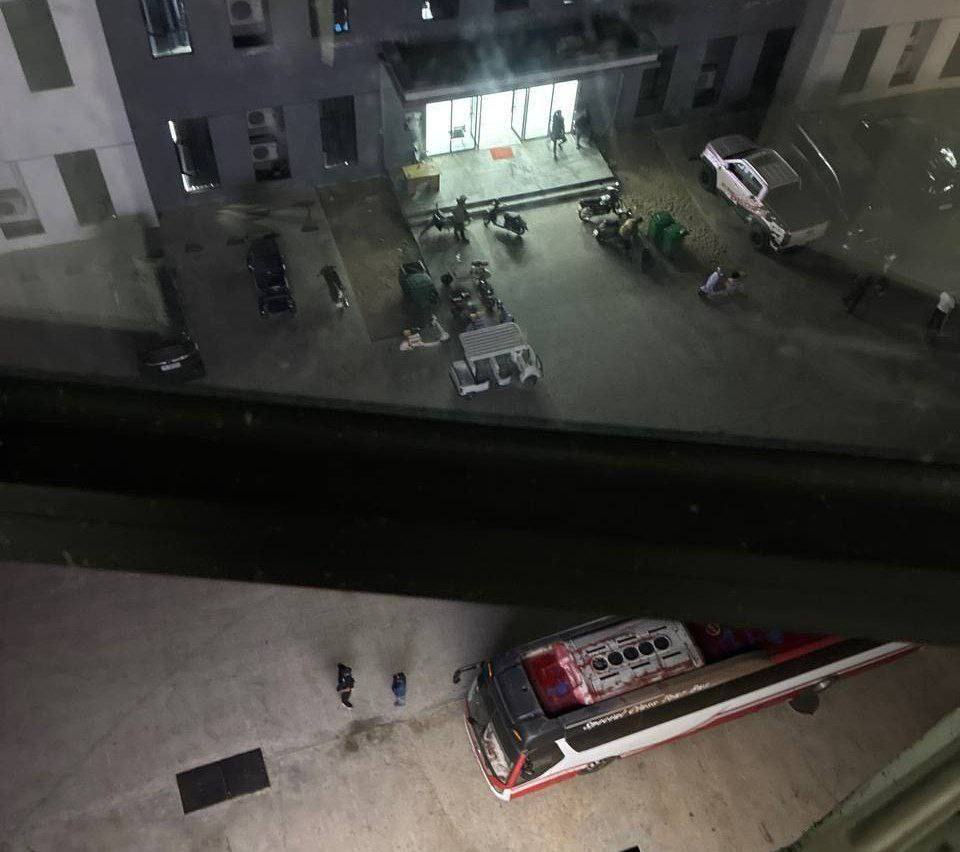

The sense of security in Chey Thom collapsed rapidly after 7 January 2026, when Prince Group CEO Chen Zhi was arrested and extradited to China. Many who had only recently arrived from the border began leaving again almost immediately. Within hours, buses were seen loading late at night, groups moved with little coordination, and individuals carried only small bags. Several buildings in Chey Thom are linked to Prince Group through ownership or development ties, and this connection had led many to assume the district offered greater stability after the conflict along the Thai border. Once Chen Zhi was detained, that perceived layer of protection evaporated. The shift in sentiment was swift and decisive, triggering immediate departures as tenants concluded the area could no longer provide the security they had expected.

Two main routes emerged in the days that followed. The first led toward the Vietnam border, especially along the Bavet corridor and nearby informal crossing points. Transport volume increased noticeably in this direction, with small groups leaving at irregular intervals. The second route involved a flow back toward Dara Sakor and Long Bay—areas widely documented in international reporting as high-risk zones associated with forced-labor cases. Although Dara Sakor carries a heavy history, some groups saw it as familiar terrain and returned there instead of remaining in Chey Thom.

At the same time, Pailin Dara Sakor and parts of Vietnam border zone experienced less visible movement and fewer disruptions. These areas are currently perceived as relatively stable compared to Chey Thom, though this reflects temporary sentiment rather than guaranteed safety.

Rumors, Unverified Notices, and Financial Tension Add Pressure

Social media further accelerated the exodus. A netizen shared what appeared to be a notice from Kaibo in Sihanoukville instructing tenants to vacate by 17 January. The authenticity of the notice has not been verified, and the building has not released any official statement. However, once the screenshot circulated online, it added to the pressure on groups already unsettled by Chen Zhi’s extradition.

Financial instability intensified the movement. Huione Pay’s rebrand to H-Pay did not restore confidence, and users continued reporting frozen balances and withdrawal delays. Even after some small withdrawals resumed, distrust remained strong. For operators dependent on fast liquidity, interruptions during a volatile period contributed to the decision to relocate again.

By mid-January, the landscape had shifted twice within a period of just weeks. The December border conflict drove people from O’Smach and Poipet into Chey Thom. The January extradition shock drove them out again, sending groups toward the Vietnam border, back to Dara Sakor, or into quieter provinces like Pailin and Mondulkiri. The result is a fragmented, unstable pattern of movement shaped by fear, rumor, and the collapse of perceived safe zones.

What happens next remains uncertain. No official enforcement announcements have been linked to these shifts, and authorities have not clarified the underlying causes. The next few weeks will show whether the current dispersal settles or whether another wave of movement reshapes the landscape once again. The situation has also revived an older regional concern: if pressure continues to build inside Cambodia, will some networks shift into Myanmar, repeating the familiar cycle of relocation that occurs whenever conditions change? There is no confirmed movement in that direction, but the possibility is being openly discussed by analysts who have seen similar patterns unfold in previous years.